When the public does science

Over the past 20 years, thousands of players of the online game Foldit have helped solve stubborn problems in protein folding. These problems exceeded the capacity of professional scientists but were also too difficult for computers to solve. This project and the subsequent work on protein design culminated in a 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for its founder, David Baker. Just one example of thousands of “crowd science” projects, Foldit illustrates how crowds can make significant contributions to scientific discovery and, by doing so, help make the world a better place.

With an international team of collaborators, I study how and when crowds best contribute to science, and how organizations can build projects that achieve scientific results while also helping better connect science with society. My book with Marion K. Poetz (Copenhagen Business School) distills these insights into a practical guide for professional scientists, contributors, policy makers, and funding agencies who need to better leverage resources to move science forward.

What crowd science is

Crowd science – also called citizen science – invites people outside formal research institutions to contribute to real research. Examples span biomedicine (Foldit, EteRNA), astronomy (Galaxy Zoo, Planet Hunters), biodiversity (eBird), the humanities (AncientLives, Glyph) and the social sciences (IPRoduct, #YouTubeRegrets). In each case, the crowd’s effort is embedded in a broader research workflow that ensures quality and effectiveness.

While many well-known projects emphasize data collection or processing, crowds can contribute across the entire research cycle – from defining questions and designing experiments to collecting data, analyzing results, and even writing and presenting findings. In the process, crowd members contribute not only knowledge but also decisions that reflect their needs and preferences. These perspectives are especially valuable for complex societal problems or emerging needs, where solutions depend not only on hard facts but on prioritizing competing goals and understanding public concerns. The COVID-19 pandemic and the transition to green energy are just two recent examples.

Why this matters now

We face complex, data-hungry problems and patchy trust in scientific institutions. Crowd science can help on both fronts.

Evidence at scale, with context. Crowds generate observations and judgments that are hard to capture otherwise: local air quality at street level, satellite classifications over vast areas, or feasibility ratings from frontline practitioners.

Participation that builds capability. Doing science together strengthens skills we need in democratic life, such as asking better questions, weighing trade-offs, and using evidence in decisions.

Navigating disruptive change. Science drives disruptive shifts in areas such as genetic modification, energy systems, or artificial intelligence and automation. With diverse participation in research, crowd science can help the broader public to detect and influence such developments earlier, test options in the wild, and legitimize choices through transparent processes.

Five ways crowds create value

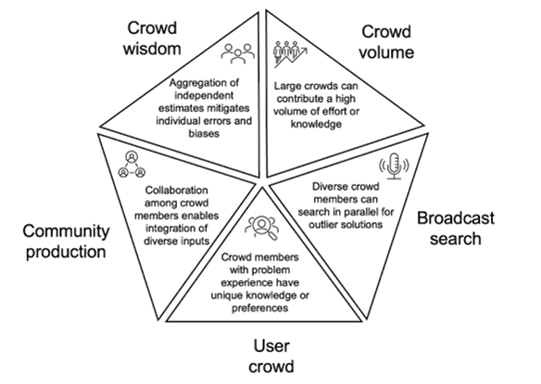

A key insight from our book is that successful projects first identify how the crowd can best contribute to solving a problem. Across hundreds of cases, we identify five distinct paradigms, each requiring different design choices.

Crowd Volume — many hands across space and time

The crowd contributes countless small, independent efforts that gain power in aggregate, such as biodiversity observations or galaxy image labels. Value comes from scale and coverage. The task for organizers: recruit widely, reduce friction, and sustain participation.

Broadcast Search – open calls for rare ideas or solutions

This model seeks valuable outliers by inviting diverse participants to propose solutions. Success depends on variety, not volume. Organizers should use broad outreach, neutral screening, and expert review.

User Crowd – experiential knowledge from those who live the problem

Participants such as patients, teachers, and frontline workers share contextual knowledge often missing in formal studies. Organizers must translate expert concepts into clear prompts and demonstrate how participants’ input informs outcomes.

Community Production – collaboration among participants

Here, contributors co-develop analyses, tools, and norms through dialogue and iteration. Effective design requires governance, moderation, and systems that recognize collective effort.

Crowd Wisdom – aggregating many independent judgments

Independent judgments from many contributors can combine to yield more accurate and stable conclusions than most individuals alone. This advantage depends on diversity and independence—if people imitate one another, the wisdom fades. Organizers must safeguard these conditions by preventing herding, recruiting varied perspectives, and using aggregation methods that surface bias and uncertainty.

The role of AI

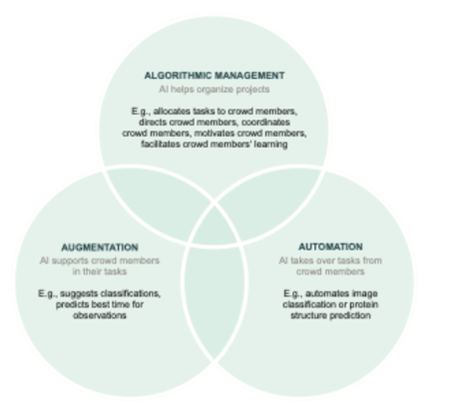

Do we still need crowds in the age of AI? In a new working paper with my ESMT colleague Linus Dahlander, we argue the answer depends on which crowd paradigm organizations seek to leverage. More generally, however, AI affects crowds in three ways:

Automate. AI handles routinized digital tasks such as classifying common images or transcribing text. This reduces latency and frees people for novelty and edge cases. While a fixed amount of work can be done with fewer people, the amount of work is often endless – making crowds more valuable as creators of training data that AI can then scale efficiently.

Augment. AI improves human contributions by providing initial ideas, background information, or interactive brainstorming. Good augmentation helps contributors make better judgments and learn over time, while lowering participation barriers – potentially increasing involvement.

Manage. AI supports algorithmic management: dividing work, matching tasks to people, coordinating handoffs, motivating participation, and offering micro-training. This raises throughput and consistency, better uses precious human time, and enriches the experiences of contributors.

Used thoughtfully, AI increases efficiency (speed, scale, quality, human time saved) and improves contributor experience (clearer feedback, skill-building, meaningful tasks). Organizations must address concerns: automation bias and over-reliance, opaque model decisions, fairness in task allocation and credit, and potential deskilling if augmentation does not foster learning.

In a new project with PhD candidate Max Koehler, we observe that AI adoption depends not only on the costs and technological capabilities of AI relative to humans. It also depends on whether organizations pursue “human-centered” goals that require active human involvement – providing jobs, enabling learning, or building scientific trust through participation.

The broader insight is fundamental: AI diffusion is not automatic – organizers and managers make conscious choices on whether and how to use AI, ideally balancing potential short-term efficiency gains with other, longer-term goals.

From research to practice

Our book is both a synthesis of research and a practical guide. It translates years of studies and case comparisons into tools that can be applied immediately: the five crowd paradigms, a set of design checklists, and canvases that organizers can use in short design sprints. The goal is to shorten the distance between idea and implementation.

We are also building capacity through workshops, for example at Buch Wien Messe and Berlin Science Week. Many of the tools were developed in the classroom – including with PhD neuroscientists at the Einstein Center Berlin – stress-tested on real projects, and improved before inclusion in the book.

A call to action

When we involve more people in doing and deciding science – with the right designs and guardrails – we get better research, faster learning, and institutions that more people can trust. That is an idea that works.

If this resonates, take two simple steps: Volunteer as a participant in a crowd- or citizen science project, choosing something that matches your interests – biology, space, mobility, education, or public policy. And read our book to see how you or your organization can use crowds in science or innovation. It is available for free at www.sciencewithcrowds.org.

ESMT Update Winter 2025