Germany’s regulatory reckoning

Germany’s political processes produce more than just decisions. They’re generating paper—tens of thousands of pages of it. And for the first time, the extent of that paperwork has been made visible.

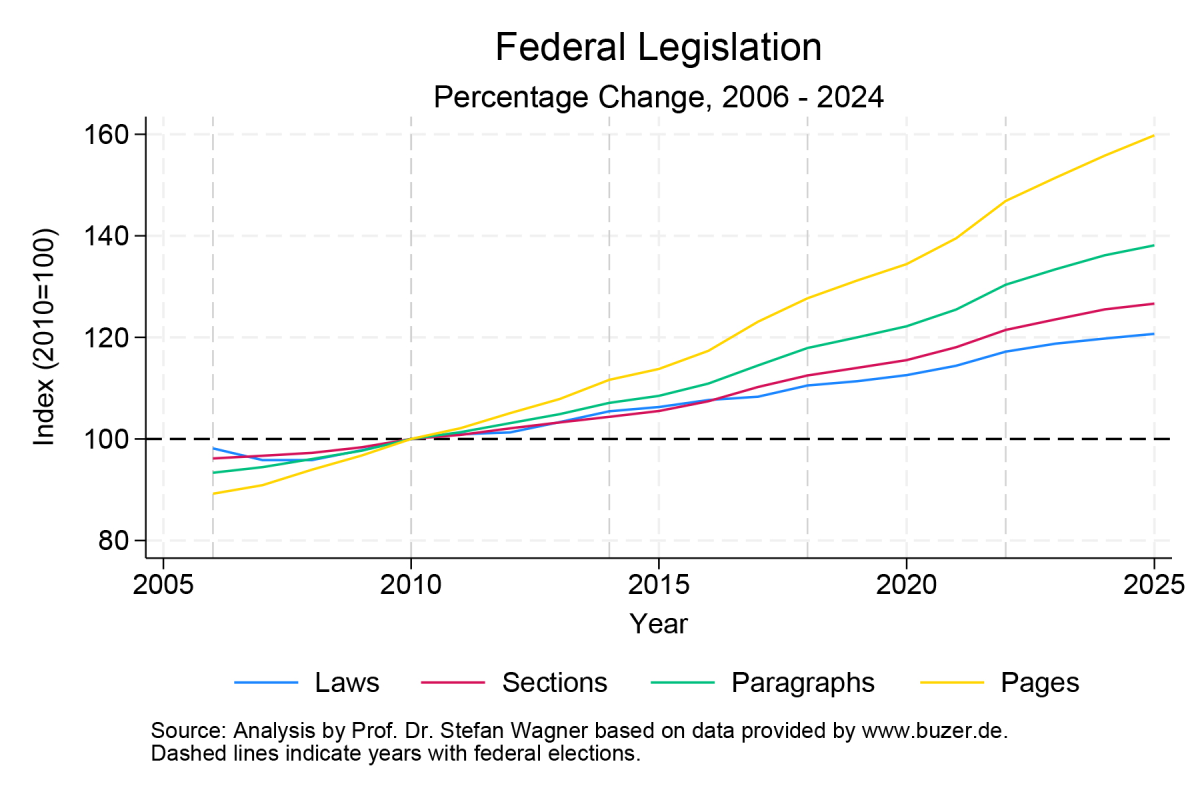

An empirical analysis by Professor Dr. Stefan Wagner of the University of Vienna, developed in collaboration with ESMT Berlin and the legal platform buzer.de, has created the bureaucracy index, a clear, data-driven measure of the country’s ballooning federal legal code. The numbers are staggering: between 2010 and 2024, the volume of federal legislation in Germany grew by around 60 percent. Despite repeated political pledges to cut red tape, the legal landscape continues to expand – both in length and complexity.

A new approach to measuring legal volume

Rather than measuring public sentiment or regulatory cost, the bureaucracy index focuses on structure. It counts the total number of characters in all federal laws and converts them into Normseiten, standardized pages of legal text (1,500 characters each, including spaces). The data, drawn from buzer.de, includes only federal statutes, excluding ordinances, EU directives, and state-level laws.

The result is a year-by-year view of the federal legal framework. The index uses 2010 as its baseline (set to 100). By the end of 2024, Germany’s federal law comprised 39,536 Normseiten – up from 24,775 in 2010. That’s an increase of more than 14,700 pages. The number of individual laws also rose during that time, from 1,133 to 1,367 statutes.

Bureaucracy’s growing cost

The economic consequences are hard to overstate. Excessive bureaucracy costs Germany up to €146 billion annually in lost economic output, according to a 2024 study by the ifo Institute commissioned by the Chamber of Industry and Commerce for Munich and Upper Bavaria. The study estimated that bringing Germany’s public administration up to Denmark’s level of digitalization could boost the country’s annual economic output by €96 billion. The total cost of bureaucracy identified in the ifo study – encompassing both direct and indirect burdens – is more than twice the €65 billion in direct compliance costs estimated by Germany’s National Regulatory Control Council.

These aren’t abstract figures. In a 2024 study by ZEW, Germany ranked 20th out of 21 OECD countries when it comes to administrative efficiency in exports. Completing a standard export transaction in Germany requires 37 hours of bureaucratic processing. In twelve other countries, the same task takes just one hour.

Wagner is blunt in his assessment: “Regulation in Germany is not decreasing – it is increasing. As a result, the country has become less and less attractive as a business location.”

Caption: Professor Dr. Stefan Wagner

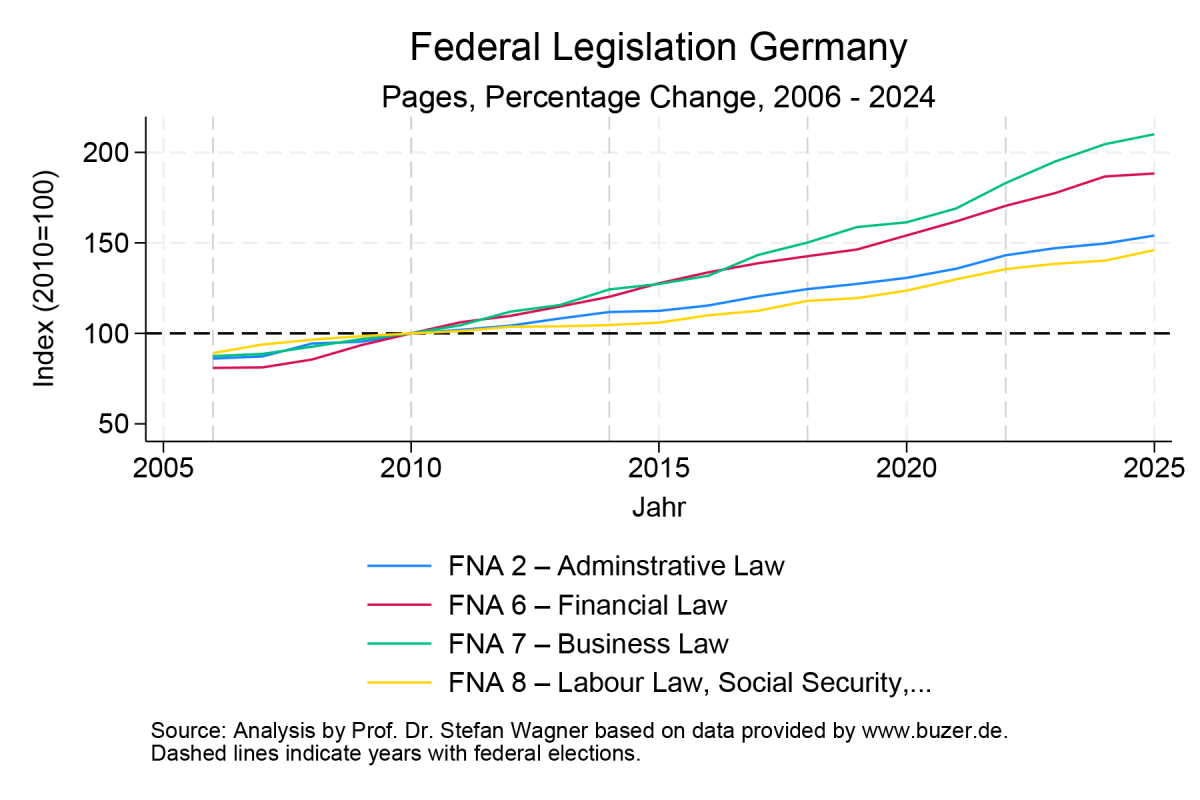

Where the law grew most

The rise in legal volume is uneven across sectors, but two areas stand out: Since 2010, the volume of business law has more than doubled, increasing by 104 to 110 percent. Financial regulation grew by 88 percent over the same period.

According to Wagner, these shifts reflect major waves of legislation. In financial law, post-2008 reforms brought new supervisory structures, transparency requirements, and EU-mandated rules. In business law, growth stems from Germany’s thorough implementation of EU regulations covering consumer rights, the digital single market, and energy governance.

Other areas expanded more moderately. Administrative law grew by 54 percent; social law by 46 percent. Even with slower growth, the Sozialgesetzbücher (Social Codes I–XII) remain the most extensive body of law by volume.

Global trend with national character

Germany’s legal expansion is part of a broader international pattern. The US Federal Register, a proxy for federal regulatory output, has exceeded 70,000 pages annually for over two decades. In the EU, the Acquis Communautaire has grown from a few hundred legal acts in the 1950s to more than 100,000 pages of binding legislation.

What sets Germany apart is its thoroughness. According to Wagner, Germany tends to implement EU directives “more comprehensively” than other member states, often adding its own specifications. The emergence of complex policy areas like digital compliance, climate regulation, and data protection has further added to the load.

A political commitment to reform

By Martin Rulsch, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link to file

Acknowledging the mounting regulatory burden, the new governing coalition of the CDU/CSU (Christian Democratic Union and Christian Social Union) and SPD (Social Democratic Party) has proposed an Immediate Action Program for Bureaucracy Reduction. The reform proposals include:

- a 25 percent reduction in compliance costs for businesses (roughly €16 billion)

- a €10 billion reduction in administrative burden for public and private actors

- elimination of compliance officer requirements for SMEs by the end of 2025

- faster approval procedures

- expanded digital services in government administration

These are ambitious goals, but Wagner’s data shows that past commitments have often been followed by further legal expansion. The gap between political intention and bureaucratic reality remains a challenge.

The complexity paradox

There’s a familiar irony at work. Laws meant to simplify or modernize governance often add new layers of complexity. A new reporting requirement here, a compliance checklist there – over time, they accumulate. Cutting red tape was also among the key promises of the "Ampel" coalition, yet the index has continued to rise, increasing by a further 2.5 percent over the previous year. The result is a system in which nearly 40,000 standardized pages of law define how the German state functions.

The bureaucracy index doesn’t judge whether those laws are good or bad. It doesn’t assess fairness, necessity, or public support. But it does provide a transparent, neutral gauge of the regulatory burden Germany is placing on itself.

Plans are already underway to expand the index. Future versions may include federal ordinances (Rechtsverordnungen), which often contain even more granular regulatory detail. There is also interest in adding state-level laws and eventually linking the index to qualitative data, such as business satisfaction surveys and regulatory impact assessments.

A tool for better governance

Wagner describes the index as a “Frühwarninstrument,” an early warning system. It shows how quickly legal density is increasing and provides policymakers with the data they need to understand the system’s direction.

It also surfaces a critical question: Is the growth of regulation outpacing our ability to manage it?

The bureaucracy index doesn’t offer solutions. But it does offer a mirror. What Germany chooses to do with what’s reflected remains to be seen.