DEEP = Different

Tailored for Depth

Recognizing that deep tech demands more than traditional startup strategies, we focus on de-risking technologies through vertical and stage specific interventions.

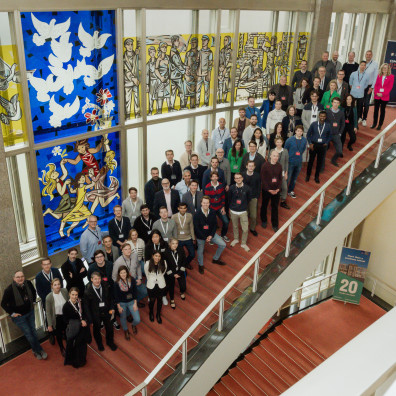

International Network

Through strategic alliances with established industrial and governmental actors as well as an extensive global network, we enable cross-industry innovation and breakthrough commercialization of research.

Proven Track Record

We offer unparalleled access to a broad alumni network of top-tier deep tech startups across diverse key industries.

Multidisciplinary Expertise Enabling Innovation

Our team of seasoned entrepreneurs and domain experts bridges the gap between science and business by understanding and navigating the unique challenges and opportunities in each vertical.

We work with the Deepest

Nowhere else can you work alongside such a remarkable group of genuine, successful entrepreneurs, investors, corporate leaders, and researchers.

Our Verticals = Our Expertise

Lifescience

LAUNCHED 2022

Addressing most challenging human diseases and promoting human longevity; leveraging innovation in:

- Therapeutics

- Diagnostics

- Medical Devices

Natural Capital

LAUNCHED 2024

Addressing the challenges in conserving and utilizing natural resources; leveraging innovation in:

- Sustainable resource management

- Waste reduction & circular economy

- Ecosystem restoration and biodiversity conservation

# DEEP x Series & Corporate Venturing

Compute

LAUNCHED IN 2024

Addressing the challenges in next generation computing and leveraging innovation in:

- New, advanced computing concepts (quantum, photonics, neuromorphic)

- Artificial Intelligence

- Resource-efficient computing solutions

Cybersecurity

LAUNCH 2025

Addressing the challenges in the global cybersecurity landscape and leveraging innovation in:

- New, advanced cybersecurity tools and protocols

- Cyber risk mitigation and threat elimination

- Resilient cybersecurity infrastructure & defense mechanisms

# DEEP Research

Food

LAUNCH PLANNED 2025

Addressing the challenges in transforming the global food system and leveraging innovation in:

- New, healthy foods and ingredients

- Food waste elimination

- Resilient food production & biomanufacturing

Our Programs = Our Impact

DEEP Qatar: Expanding deep-tech innovation to the Middle East

DEEP Qatar is the result of the long-standing partnership between ESMT Berlin, the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) and the Qatar Research, Development, and Innovation Council (QRDI). Based in Doha, it brings together researchers, founders, and investors from Germany and Qatar and supports science-driven entrepreneurship through programs such as DEEP Academy, DEEP Pioneers, and the Creative Destruction Lab.

We go deep = Our Research

DEEP Research

We get from anecdotal to actual evidence.

Our think and action tank is embedded in ESMT’s world-class faculty and strong scientific community. Through the Joachim Faber Chair in Business and Technology, we are creating evidence around deep tech innovation and developing policy recommendations.

DEEP People

DEEP Initiators & Supporters

Jörg Rocholl

Joachim Faber

Marco Janezic

Matthias Koch

Our partners and supporters

Companies and institutions we have worked with