Science for equity: Lessons from the Virchow Prize Lecture at ESMT Berlin

In 2002, a traditional chief in rural KwaZulu-Natal faced a crisis. “I see 15 to 20 funerals each day,” he told researchers who had come to his community. “What kind of leader am I if I have nobody left to lead?”

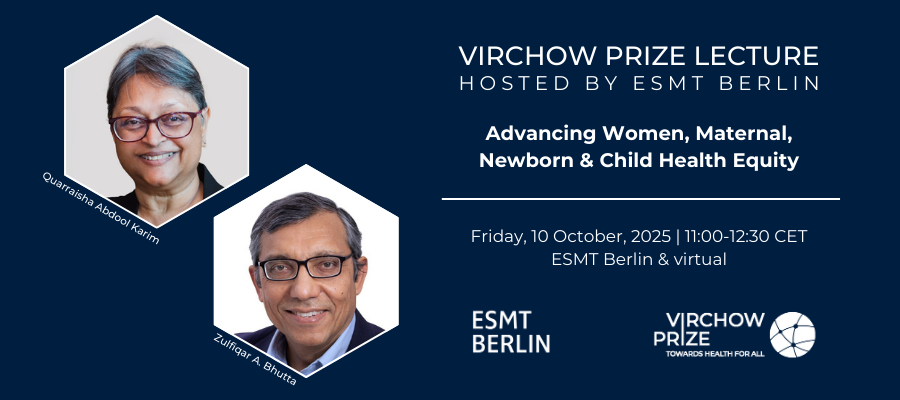

That conversation became a turning point in HIV prevention research – and it exemplified the approach honored at ESMT on October 10, when the school hosted the 2025 Virchow Prize Lecture. Named for the 19th-century physician who defined medicine as a social science, the Virchow Prize celebrates research that advances health and justice alike. This year’s laureates – Prof. Quarraisha Abdool Karim and Prof. Zulfiqar A. Bhutta – demonstrated how rigorous science translates into policy impact when grounded in community partnership.

ESMT President Jörg Rocholl emphasized the alignment between the prize and the school’s mission: developing responsible leaders who bridge research and practice. “Transformative change is possible when leadership is grounded in evidence, community engagement, and an unwavering commitment to justice,” he said. Since 2015, ESMT has collaborated with the World Health Summit to train more than 240 young clinicians from over 90 countries. The laureates’ lectures – published simultaneously in The Lancet for the first time – offered a framework for how that leadership operates in practice.

Opening remarks were delivered by Prof. Detlev Ganten, co-founder and member of the board of trustees of the Virchow Foundation, who reflected on the prize’s origins and its mission to link science and social responsibility, and by Prof. Ole Petter Ottersen, vice president of the Virchow Foundation and former president of Karolinska Institutet, who framed the lectures within Rudolf Virchow’s legacy of medicine as a social science.

When evidence meets community need

The chief’s call for help grounded three decades of Abdool Karim’s HIV prevention work. In the late 1980s, her population-based surveys revealed a striking pattern: HIV prevalence was below one percent overall, yet infection rates among young women aged 15–19 were several times higher than among young men. Genetic sequencing confirmed that young women were acquiring HIV from older men, sustaining the epidemic.

Prevention required more than epidemiological insight – it required agency. As one woman challenged the researchers: “You scientists are so smart – why don’t you develop something we can use?”

When Abdool Karim’s team at the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA) proposed testing tenofovir gel in a before-and-after sex regimen, critics called the design “doomed by design.” The 2010 Vienna announcement proved otherwise: the gel reduced HIV infection, establishing proof of concept for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Science named it one of the year’s top 10 breakthroughs. Today, daily oral PrEP is available in over 100 countries. Next-generation approaches show even greater promise: long-acting injectables administered twice yearly demonstrate near 100 percent protection in trials.

The CAPRISA model itself exemplifies inclusive scientific leadership. Eighty percent of the center’s team are women, from senior leadership to data analysis – a composition that has strengthened both its research and its impact. “When communities co-own the knowledge being created,” Abdool Karim explained, “the transition from science to policy to practice happens naturally.”

Reaching those left behind

Bhutta’s lecture built on this theme with evidence from South Asia. When he returned to Pakistan in 1985, he found not one country but five, divided by poverty and access to care. The 2006 Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey revealed the depth of the challenge: among the poorest couples, fewer than one in three had discussed where they would give birth. Half of newborn deaths occurred at home without care. The barrier was not only material poverty but, as Bhutta put it, “poverty of hope and imagination.”

Three evidence-based strategies proved effective. Conditional cash transfers for women, tied to prenatal visits and child immunization, achieved among the fastest reductions in low birth weight and stunting anywhere. A nationwide network of Lady Health Workers reduced neonatal mortality by 15 percent by expanding antenatal care and facility deliveries. In urban Karachi, mapping unimmunized children revealed concentrated clusters in poor settlements; tailored interventions then closed those gaps within two years.

“The eye does not see what the mind does not know,” Bhutta emphasized. Effective targeting requires that equity data become part of routine health systems. His analysis of high-performing countries revealed a consistent pattern: successful nations invest deliberately in social determinants. Employment, education, and women’s empowerment account for nearly half of improvements in child survival and nutrition. During the Millennium Development Goals period, unified global commitment drove child deaths from ten million to just above six million – the fastest improvement in history.

Yet Bhutta warned of a new threat: what he termed “the ideological determinant of health.” When misinformation erodes trust in vaccines and scientific expertise, ideology itself becomes a structural barrier to progress.

Confronting ideology with leadership

The panel took up that challenge, exploring how scientific leadership must confront misinformation and political resistance as much as disease. Dr. Rana Hajjeh, former president of the Population Council, challenged scientists to move beyond technical expertise. “I understand political realities – but I will never let politics trump public health,” she said. Health interventions succeed when they engage not only health ministers but also those responsible for finance, education, and environment.

Dr. Mariam Jashi, CEO of the Global Sepsis Alliance, reinforced the importance of domestic ownership. During her tenure as Georgia’s deputy minister of health, the country achieved universal coverage at approximately $150 per capita. “International aid can be catalytic,” she noted, “but it cannot replace national responsibility.”

Both laureates underscored that lasting progress depends on leadership able to connect research, policy, and implementation. Abdool Karim emphasized advocacy that builds ownership from the outset, while Bhutta highlighted the power of deliberate investment in the most disadvantaged communities. Their shared lesson: evidence drives change only when leaders can navigate both science and systems.

Refusing habituation

Bhutta closed by invoking Rudolf Virchow’s warning: humanity learns to tolerate even the most horrible situations by habituation, forgetting the shame of injustice in daily routine.

The Virchow Prize, established in 2021 on the 200th anniversary of Virchow’s birth, was designed to counter that habituation. For ESMT, hosting the lecture reflects a commitment to leadership that extends beyond business strategy to encompass social responsibility.

The lessons from this year’s laureates offer three core principles for responsible leadership in complex systems. First, effective interventions require community partnership, not top-down implementation. Second, progress accelerates when the most vulnerable are reached first. Third, evidence translates into policy when scientists engage political and financial institutions strategically – and refuse to let ideology override data.

As Hajjeh put it, “Silence in the face of inequity is also a form of violence.” For institutions committed to developing leaders who make a difference – for business and society alike – that principle is not aspirational. It is operational.